I came across an interesting bit of folklore today. The Dutch Renaissance writer Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) reported in his Colloquies that snakes in Italy love milk, hate garlic, and will crawl down your throat while

you’re sleeping and take up residence in your stomach, but lizards are

friendly to humans and will warn you about them. It's an origin myth explaining why peasants love garlic and snakes and lizards are enemies, but I don't know if its origins are in actual folk belief, or if it's a different sort of popular story. Or some combination of the two. I can't find any other source for those snippets of story, but Erasmus did study in Italy so it's possible that belief existed there at one time.

From The Whole Familiar Colloquies of Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, translated by Nathan Bailey, 1877, pg. 388-9, Concerning Friendship: Ephorinus and John.’

The largest Italian lizard species I can find is the Italian wall lizard, Podarcus sicula - which is also the most abundant lizard species in Italy. They're up to 3.5 inches (9cm) long, so not very large.

Erasmus was an interesting guy who lead a busy life; he was the illegitimate child of a priest and a woman who was possibly his housekeeper who lost his parents to the plague and was pressed into monasticism by poverty. He later left the monastery to become a secretary, and was permanently released from his vows by the Pope, which was unusual. He was ordained as a Catholic priest at the age of 25, although he doesn't seem to have worked as one much. He studied at the University of Paris on a stipend and then the University of Turin and became a classical scholar and prominent Christian Humanist thinker and popular writer.

He was a professor at Cambridge at one point and complained about the lack of wine:

Later editions of his New Testament were used by Martin Luther as a basis for his German translation, and probably also by Tyndale for the first English New Testament and by Stephanus for the English version that the translators of the King James Version based their text on.

By the 1530s, the writings of Erasmus accounted for 10 to 20 percent of all book sales in Europe.[63]

He died suddenly from dysentery in Basel, Switzerland in 1536.

A little bit about his Colloquies, from Wikipedia:

From The Whole Familiar Colloquies of Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, translated by Nathan Bailey, 1877, pg. 388-9, Concerning Friendship: Ephorinus and John.’

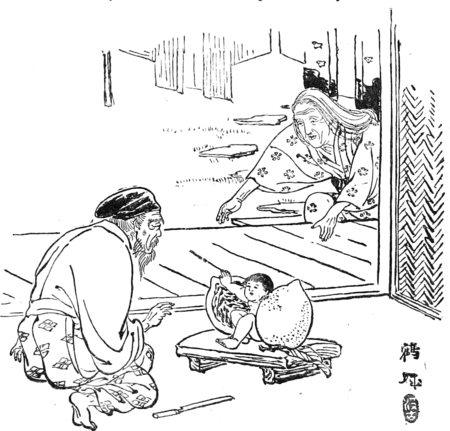

Ep. Do you know the lizard?

Jo. Why not?

Ep. There are very large green ones in Italy. This creature is by nature friendly to mankind, and an utter enemy to serpents. […]

The husbandmen of that place related to us a wonderful strange thing for a certain truth; that the countrymen being weary sometimes, sleep in that field, and have sometimes with them a pitcher of milk, which serves both for victuals and drink; that serpents are great lovers of milk, and so it often happens that they come in their way. But they have a remedy for that.

Jo. Pray, what is it?

Ep. They daub the brims of the pitcher with garlic, and the smell of that drives away the serpents.

Jo. What does Horace mean, then, when he says garlic is a poison more hurtful than henbane, when you say it is an antidote against poison?

Ep. But hear a little, I have something to tell you that is worse than that. They often creep slily into the mouth of a man that lies sleeping with his mouth open, and so wind themselves into his stomach.

Jo. And does not a man die immediately that has entertained such a guest?

Ep. No, but lives most miserably; nor is there any remedy but to feed the man with milk, and other things that the serpent loves.

Jo. What, no remedy against such a calamity?

Ep. Yes, to eat an abundance of garlic.

Jo. No wonder, then, mowers love garlic.

Ep. But those that are tired with heat and labour have their remedy another way; for, when they are in danger of this misfortune, very often a lizard, though but a little creature, saves a man.

Jo. How can he save him?

Ep. When he perceives a serpent lying perdue in wait for the man, he runs about upon the man’s neck and face, and never gives over till he has waked the man by tickling him, and clawing him gently with his nails; and as soon as the man wakes, and sees the lizard near him, he knows the enemy is somewhere not far off in ambuscade, and looking about seizes him.

Jo. The wonderful power of nature!Wonderful indeed.

The largest Italian lizard species I can find is the Italian wall lizard, Podarcus sicula - which is also the most abundant lizard species in Italy. They're up to 3.5 inches (9cm) long, so not very large.

|

| Podarcis sicula on a dry branch near Urbino in Tuscany (Florian Prischl/Wikimedia Commons). |

|

| Podarcis sicula found in Los Angeles county. They're very adaptable and have been introduced to part of the US and North Africa (California Herps). |

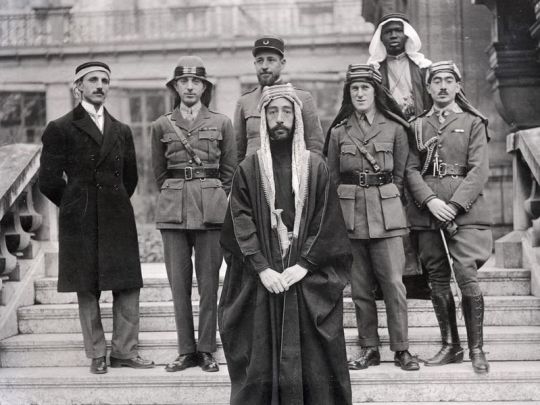

Erasmus was an interesting guy who lead a busy life; he was the illegitimate child of a priest and a woman who was possibly his housekeeper who lost his parents to the plague and was pressed into monasticism by poverty. He later left the monastery to become a secretary, and was permanently released from his vows by the Pope, which was unusual. He was ordained as a Catholic priest at the age of 25, although he doesn't seem to have worked as one much. He studied at the University of Paris on a stipend and then the University of Turin and became a classical scholar and prominent Christian Humanist thinker and popular writer.

|

| A 1523 portrait of Erasmus by Hans Holbein the Younger, who painted him several times (Wikimedia). |

He was a professor at Cambridge at one point and complained about the lack of wine:

At the University of Cambridge, he was the Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity and had the option of spending the rest of his life as an English professor. He stayed at Queens' College, Cambridge from 1510 to 1515. His rooms were in the "I" staircase of Old Court, and he famously hated English ale and English weather. He suffered from poor health and complained that Queens' could not supply him with enough decent wine (wine was the Renaissance medicine for gallstones, from which Erasmus suffered). Until the 19th century, Queens' College used to have a corkscrew that was purported to be "Erasmus' corkscrew" which was a third of a metre long, though today the college still has what it calls "Erasmus' chair." (Wikipedia)In the early sixteenth century, Erasmus produced a critical edition of the New Testament, including the late Greek texts and facing them a more polished Latin translation and his own notes, saying "It is only fair that Paul should address the Romans in somewhat better Latin."[32]

Later editions of his New Testament were used by Martin Luther as a basis for his German translation, and probably also by Tyndale for the first English New Testament and by Stephanus for the English version that the translators of the King James Version based their text on.

By the 1530s, the writings of Erasmus accounted for 10 to 20 percent of all book sales in Europe.[63]

He died suddenly from dysentery in Basel, Switzerland in 1536.

A little bit about his Colloquies, from Wikipedia:

Colloquies is one of the many works of the “Prince of Christian Humanists”, Desiderius Erasmus. Published in 1518, the pages “…held up contemporary religious practices for examination in a more serious but still pervasively ironic tone”. […]

The Colloquies is a collection of dialogues on a wide variety of subjects. They began in the late 1490s as informal Latin exercises for Erasmus’ own pupils. In about 1522 he began to perceive the possibilities this form might hold for continuing his campaign for the gradual enlightenment and reform of all Christendom. Between that date and 1533 twelve new editions appeared, each larger and more serious than the last, until eventually some fifty individual colloquies were included ranging over such varied subjects as war, travel, religion, sleep, beggars, funerals, and literature. All of these works were in the same graceful, easy style and gentle humor that made them continually sought as schoolboy exercises and light reading for generations.They are humorous, and very entertaining. I've downloaded that pdf from Google Books and will probably read more of it, unless I forget.