My grandma died about ten years ago, and there's very little left in her garden besides grass and plants that are considered weeds. I was startled when I came back to Canada, because I had been looking forward to seeing it again, and it was nothing like I remembered. Only the empty beds were left. One more piece of her had disappeared while I wasn't looking.

This is Geranium molle, native to the Mediterranean and now a lush carpet covering filling what used to be the lawn around our raised vegetable beds. The grass is pretty much gone. I didn't really notice it before the leaves started to turn red, but I think it's rather pretty. There's some buttercups in there too, and also a Galium species (cleavers or bedstraw), I can't tell which. It doesn't quite look like G. aparine but I looked through a lot of botanical literature and I can't find any closer species. It may or may not be native to North America, but it is edible in small quantities (large quantities have a mild laxative effect).

My grandma had a bed of a cultivated Galium species, sweet woodruff, next to the front walk, but it's almost entirely gone now. What little is left probably won't last much longer.

What plants are weeds and what are proper plants seems to be a matter of opinion, and of desire for the plant, and of frustration with it. Especially if it's introduced. Most of the plants left in my grandma's garden are foreign, and considered noxious or invasive weeds, undesirable - but then, the prettier plants that she cultivated and loved were introduced too. They just weren't resilient enough or suitable enough for this climate to survive after she was gone.

Rather a lot of the plants left in the garden turn out to be edible. There's also tall amaranth, and broadleaf dock, whose leaves are developing reddish spots like rust:

Dock leaves can be cooked and eaten in small quantities (large quantities can be hazardous, since they contain oxalic acid), and the leaves were described being used to wrap blocks of fresh butter in Adam Bede. The seeds can be ground and eaten, but they contain a lot of chaff and there's no way to remove it.

There's sow thistle, related to dandelion, old and bitter at this time of year but edible when the leaves are young:

There's Himalayan blackberry everywhere, of course:

It produces a fair bit of fruit on second-year canes, and I'm told the leaves can be made into tea, although I haven't tried it yet.

Morning glory is everywhere:

It's not edible, and it strangles everything, but at least the flowers are pretty. The burdock had pretty purple flowers earlier, but they've been replaced by brown burrs:

Probably the most striking thing in the garden at this time of year is the rose bush. Its hips are edible too, and can be made into tea:

It's so huge and vigorous and exceptionally thorny that I suspect a more tender rose was grafted to it and didn't survive, especially since it's right next to the fence where my grandma had roses planted. I didn't notice what sort of flowers it had this spring or summer.

If Mary Lennox's secret garden were real, this is what it would look like after a decade left mostly to itself. The wildest of the roses would have survived and run rampant, and the crocuses and daffodils naturalised, but most of the cultivated plants would have disappeared and the small weedy ones that slipped in unwanted volunteered to take their places, and flourished, a carpet of green in the spring, dotted with white and yellow flowers in the summer, seed heads turning brown in the fall and leaves shading to yellow, touched with red, dotted with rust, fading to brown and falling crumpled to the ground. The plants lie dormant all winter, but finally the roots and stems spring to life again in March, as they do every year without fail.

---

For two or three minutes [Dickon] stood looking round him, while Mary watched him, and then he began to walk about softly, even more lightly than Mary had walked the first time she had found herself inside the four walls. His eyes seemed to be taking in everything—the gray trees with the gray creepers climbing over them and hanging from their branches, the tangle on the walls and among the grass, the evergreen alcoves with the stone seats and tall flower urns standing in them.

"I never thought I'd see this place," he said at last, in a whisper.

"Did you know about it?" asked Mary.

She had spoken aloud and he made a sign to her.

"We must talk low," he said, "or some one'll hear us an' wonder what's to do in here."

"Oh! I forgot!" said Mary, feeling frightened and putting her hand quickly against her mouth. "Did you know about the garden?" she asked again when she had recovered herself. Dickon nodded.

"Martha told me there was one as no one ever went inside," he answered. "Us used to wonder what it was like."

He stopped and looked round at the lovely gray tangle about him, and his round eyes looked queerly happy.

"Eh! the nests as'll be here come springtime," he said. "It'd be th' safest nestin' place in England. No one never comin' near an' tangles o' trees an' roses to build in. I wonder all th' birds on th' moor don't build here."

Mistress Mary put her hand on his arm again without knowing it.

"Will there be roses?" she whispered. "Can you tell? I thought perhaps they were all dead."

"Eh! No! Not them—not all of 'em!" he answered. "Look here!"

He stepped over to the nearest tree—an old, old one with gray lichen all over its bark, but upholding a curtain of tangled sprays and branches. He took a thick knife out of his Pocket and opened one of its blades.

"There's lots o' dead wood as ought to be cut out," he said. "An' there's a lot o' old wood, but it made some new last year. This here's a new bit," and he touched a shoot which looked brownish green instead of hard, dry gray. Mary touched it herself in an eager, reverent way.

"That one?" she said. "Is that one quite alive quite?"

Dickon curved his wide smiling mouth.

"It's as wick as you or me," he said; and Mary remembered that Martha had told her that "wick" meant "alive" or "lively."

"I'm glad it's wick!" she cried out in her whisper. "I want them all to be wick. Let us go round the garden and count how many wick ones there are."

She quite panted with eagerness, and Dickon was as eager as she was. They went from tree to tree and from bush to bush. Dickon carried his knife in his hand and showed her things which she thought wonderful.

"They've run wild," he said, "but th' strongest ones has fair thrived on it. The delicatest ones has died out, but th' others has growed an' growed, an' spread an' spread, till they's a wonder. See here!" and he pulled down a thick gray, dry-looking branch. "A body might think this was dead wood, but I don't believe it is—down to th' root. I'll cut it low down an' see."

He knelt and with his knife cut the lifeless-looking branch through, not far above the earth.

"There!" he said exultantly. "I told thee so. There's green in that wood yet. Look at it."

Mary was down on her knees before he spoke, gazing with all her might.

"When it looks a bit greenish an' juicy like that, it's wick," he explained. "When th' inside is dry an' breaks easy, like this here piece I've cut off, it's done for. There's a big root here as all this live wood sprung out of, an' if th' old wood's cut off an' it's dug round, and took care of there'll be—" he stopped and lifted his face to look up at the climbing and hanging sprays above him—"there'll be a fountain o' roses here this summer."

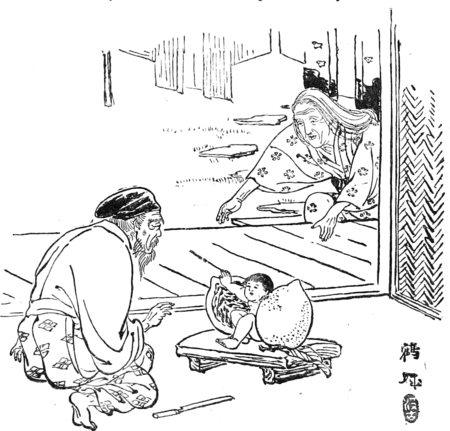

- Frances Hodgson Burnett, The Secret Garden, Chapter XI, 'The Nest of the Missel Thrush,' pg 128-9.The illustrated 1911 edition of The Secret Garden is available on the Internet Archive.