Some of this is a little inappropriate, but we could all use a laugh and it involves cats, an interesting woman from history, and a Japanese folktale.

So there are pictures circulating of Japanese internet sensation Shironeko and a cat friend doing...something with...something:

Those are real peaches; they're yellow peaches and they really are as big as they look. I'm not the only one who thinks they look like butts:

About five other commenters said the same thing. Butts! Whomever took those photos does have really great photography "put skills" (I can't think how else to phrase that), and very cooperative cats.

Someone in the comments wrote a little story about the cats and their peaches, but I have no idea what's going on:

"Bugger also topped with yellow peaches." Indeed. Thank you, Google Translate. I have no idea what word it's translating as "bugger"; it doesn't look like it's any better at translating Japanese into English than it is at translating Arabic into English.

Low-acid, fragile clingstone peaches are popular in Japan, different from the varieties popular in North America and the Middle East:

A summary of the story of Momotaro, from Wikipedia:

Wikipedia gives a little bit of information on Yei Theodora Ozaki's life, but it's all from an introduction to one of her books:

Ozaki's Wikipedia page has links to online copies of her books; they're in the public domain.

I couldn't find a whole lot of information on Japanese yellow peaches in English, but the Wall Street Journal has an article on Chinese water honey peaches, which are related:

So there are pictures circulating of Japanese internet sensation Shironeko and a cat friend doing...something with...something:

|

| (Images from Shironeko's blog, in Japanese. I also ran the post through Google Translate). |

|

| (From the comments on the original blog post. I took screenshots of the Google translation of the page). |

Someone in the comments wrote a little story about the cats and their peaches, but I have no idea what's going on:

Low-acid, fragile clingstone peaches are popular in Japan, different from the varieties popular in North America and the Middle East:

Momo (Peach) Japanese peaches are generally larger, softer and more expensive than Western peaches, and their flesh is usually white rather than yellow. Peaches are commonly eaten raw after being peeled. Japanese peaches are in season during the summer. Peaches were introduced from China as early as the Yayoi Period (300 BC- 300 AD). Peach production in the prefectures of Yamanashi and Fukushima make up the majority of the country's total output. The peach features prominently in the Japanese folklore tale of Momotaro (The Peach Boy), which is set in Okayama Prefecture.

(From Japan Guide)

A summary of the story of Momotaro, from Wikipedia:

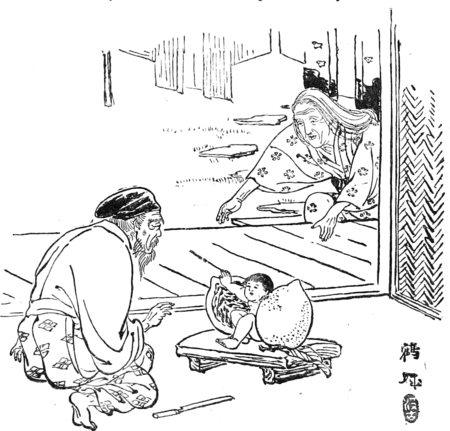

According to the present form of the tale (dating to the Edo period), Momotarō came to Earth inside a giant peach, which was found floating down a river by an old, childless woman who was washing clothes there. The woman and her husband discovered the child when they tried to open the peach to eat it. The child explained that he had been sent by Heaven to be their son. The couple named him Momotarō, from momo (peach) and tarō (eldest son in the family).[1]The whole story is in The Japanese Fairy Book (1908), written by Iwaya Sazanami, illustrated by Kakuzo Fujiyama, and translated by Yei Theodora Ozaki. It's not very long.

Years later, Momotarō left his parents to fight a band of marauding oni (demons or ogres) on a distant island. En route, Momotarō met and befriended a talking dog, monkey, and pheasant, who agreed to help him in his quest. At the island, Momotarō and his animal friends penetrated the demons' fort and beat the band of demons into surrendering. Momotarō and his new friends returned home with the demons' plundered treasure and the demon chief as a captive. Momotarō and his family lived comfortably from then on.[1]

|

| Momotaro emerging from the giant peach (illustration from The Japanese Fairy Book). |

Wikipedia gives a little bit of information on Yei Theodora Ozaki's life, but it's all from an introduction to one of her books:

Yei Theodora Ozaki (英子セオドラ尾崎 Eiko Seodora Ozaki?, 1871 – December 28, 1932) was an early 20th-century translator of Japanese short stories and fairy tales. Her translations were fairly liberal but have been popular, and were reprinted several times after her death.Cabinet des Fées has a very thorough article about Ms. Ozaki's life and environment and their influence on her work. It mentions Ms. Ozaki's desire to change contemporary Western ideas of Japanese culture, and particularly of Japanese women as oppressed and passive:

According to "A Biographical Sketch" by Mrs. Hugh Fraser, included in the introductory material to Warriors of old Japan, and other stories, Ozaki came from an unusual background. She was the daughter of Baron Ozaki, one of the first Japanese men to study in the West, and Bathia Catherine Morrison, daughter of William Morrison, one of their teachers. Her parents separated after five years of marriage, and her mother retained custody of their three daughters until they became teenagers. At that time, Yei was sent to live in Japan with her father, which she enjoyed. Later she refused an arranged marriage, left her father's house, and became a teacher and secretary to earn money. Over the years, she traveled back and forth between Japan and Europe, as her employment and family duties took her, and lived in places as diverse as Italy and the drafty upper floor of a Buddhist temple.

All this time, her letters were frequently misdelivered to the unrelated Japanese politician Yukio Ozaki, and his to her. In 1904, they finally met, and soon married.

Ms Ozaki’s biographer Mrs Fraser tells us that one of O-Yei’s motivations for writing was to dispel misconceptions of Japan that she found in the West, and to show the “good old ideals and sentiments”[6] of Japanese culture portrayed in the old stories. We are told that one of O-Yei’s particular concerns was the perception of Japanese women in the West. She wanted to put an end to the notion of the Japanese woman as an oppressed, passive Madame Butterfly figure. Mrs Fraser records her as saying: “When I was last in England and Europe… very mistaken notions about Japan and especially about its women existed generally. I determined if possible to write so as to dispel these wrong conceptions.”[7] In this way, she was very much a woman of her time. The Meiji Period (1868-1912) was a time of great social and political change in Japan, as the country was keen to show itself as equal to the Western powers. Women led the way in this as much as men; and O-Yei herself belonged to several educational, charitable and patriotic ladies’ societies. At the same time, things were changing for women in England too. The suffragettes were to riot in 1911 and the Women’s Institute was to be founded in 1915. As a well-connected, bi-cultural woman, Yei Theodora Ozaki stood in a good position to address these contemporary issues, at the same time as she looked back to the past for inspiration.

(Elizabeth Hopkinson, 'East Meets West: Yei Theodora Ozaki’s Japanese Fairy Tales,' May 2011)

Ozaki's Wikipedia page has links to online copies of her books; they're in the public domain.

I couldn't find a whole lot of information on Japanese yellow peaches in English, but the Wall Street Journal has an article on Chinese water honey peaches, which are related:

Thai bananas are long-lived compared with China's honey peaches. Picked in the morning, the peaches are flown to Beijing or trucked to Shanghai in the afternoon; in many cases, they are selling in stores the same evening. On a recent Saturday afternoon in Yangshan's wholesale peach market, I asked a grower to find me a carton of peaches that I could take home with me to Bangkok on Monday. No peach in the market would last that long, he replied; I'd have to go with him to his orchard so he could pick me hard, green ones. He warned me that I'd be sacrificing some taste because they would be picked too early. By Tuesday, the green peaches I ended up taking home with me were so soft that I had to put them all in the refrigerator. They were still delicious.There is a bit more information on Japanese and Chinese (and other) peach cultivars and breeding programs in The Peach: Botany, Production, and Uses (Layne and Bassi, 2008, pg 168-9). The ebook is over two hundred dollars, so hopefully nobody wants to read the redacted sections very badly.

Tang Haijun, a big honey peach grower and an industry spokesman, says another problem with Chinese peaches is that they are extraordinarily fragile. "They're so tender, if you press on one, in an hour there will be a black spot," he says. Over a lunch of local specialties (snails, pigs feet, pumpkin stems, his peaches for dessert), Mr. Tang explained that to keep away insects, he has every peach in his orchard individually wrapped with newspaper while it is ripening on the tree. All this special handling comes at a price: A honey peach sells for as much as $3 in a Shanghai or Beijing grocery store.

In the U.S., peach technology produces a very different product. "It's unfortunate that many of our peaches are bred to have superior shelf life and exterior color," says Karen Caplan, chief executive of Frieda's Inc., a Los Alamitos, Calif., high-end distributor of imported and domestic produce. "The growers don't focus on flavor. They refrigerate them in transit, put them on the shelf, and they go mealy." [...]

The best bet, then, is to eat honey peaches in China, and that's what I did with wild abandon, consuming 10 peaches, averaging half a pound each, in a single day in Yangshan. Under the tutelage of Mr. Tang, I learned that Chinese peach-eating is a very different process. First, you should gently massage the peach for several minutes, releasing the juice. When it starts feeling like a sponge, it's ready to be peeled; the skin slips off like a glove. Then you just pick it up whole and slurp away; cutting it would result in waste of the delicious juice. (The Best Peach on Earth, August 21, 2009)

No comments:

Post a Comment