T.E. Lawrence, British archeologist and later military officer who assisted the Arab forces against the Ottomans during the First World War, had three Arabian daggers he obtained during the desert campaigns, two silver and one gold. He gave one away, one is held by the University of Oxford, and one was bought at auction last month for nearly two hundred thousand dollars.

|

| The second silver dagger (Christie's). |

Above is the second silver-gilt jambiya dagger (30cm long), gifted to T.E. Lawrence in 1917 by Sherif Nasir at Aqaba after

the Arab capture of that town

from the Turks.

The dagger was auctioned by Christie’s on July 15, 2015, for a price realised of £122,500 (US $191,713). (The price realised is the hammer price plus the buyer's premium).

Sherif

Nasir was an Arab leader and cousin of

Emir Feisal I, a Hashemite

prince who was the third son of the Grand Sherif of Mecca, lead the forces of

the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans from 1916-18, and was appointed king of Syria and then

Iraq after the First World War. Emir Faisal commanded the Arab forces alongside Abu ibu Tayi in the Battle of Aqaba, with Sherif Nasir

participating and Lawrence advising.

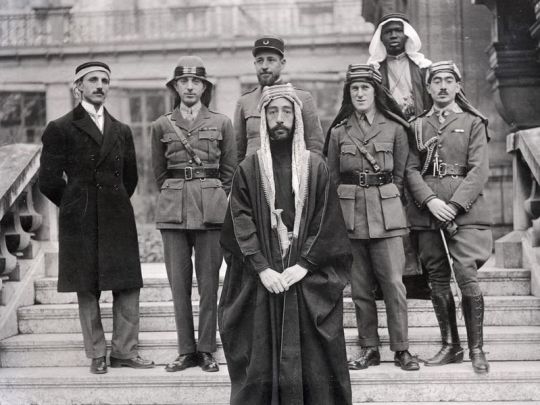

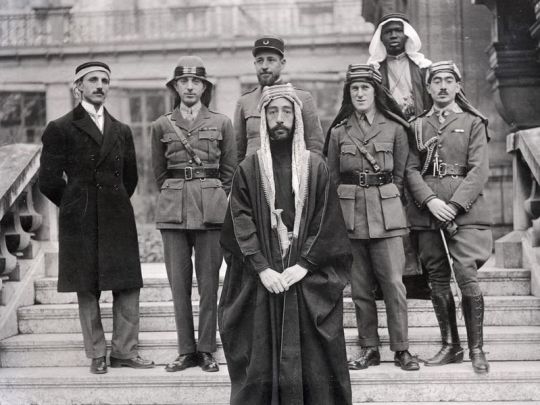

|

| Emir Faisal’s delegation at Versailles, during the Paris Peace

Conference of 1919. Left to right: Rustum Haidar, Nuri as-Said, Prince

Faisal, Captain Pisani (behind Faisal), T. E. Lawrence, unknown person,

Captain Tahsin Kadry (Wikipedia). |

In 1921, Lawrence left the dagger in the

possession of sculptor and society hostess Kathleen Scott (widow of

Antarctic explorer Captain Robert Falcon Scott), who had seen him at the

ballet and not known who he was. She would later comment to him in a

letter that when she had first seen him ‘you had a turban on and I think

I thought you had been born in it,’ which makes me wonder

why he was wearing a turban to the ballet, who does that.

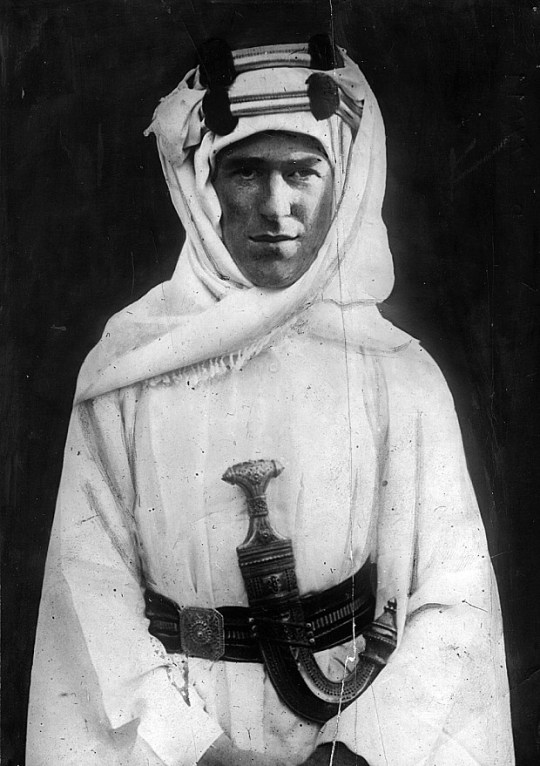

I have never seen Lawrence in a turban, and they weren’t worn by the Arabs where he was (they still aren’t),

so I suspect that when Scott saw him at the ballet he was actually

wearing a kefiyyah and agal like he did during the Arab Revolt. There

are many photos of him in one. Still, why would a Welshman wear that

at the ballet.

Scott saw him again at Waterloo station and requested a sitting so she could make a sculpture of him:

Lawrence acquiesced, stipulating only that she did not ‘do me as Colonel

Lawrence (he died Nov. 11. 1918)’. In fact, the resulting sculpture

depicted him in just this manner, in full Arab dress, dagger at his

waist. Of the sitting on 9 February 1921, Scott wrote: ‘Oh, what a very

pleasant day, first Col. Lawrence came. We had great fun about dressing

him up in his Arabian clothes, which he finally put on in the drawing

room’. After his final sitting on the 20 February, he left the present

dagger and robes with Kathleen, that she might continue her work while

he sailed to Cairo; it would be over a year later, on the 28 August

1922, that he would write to request their return – ‘There’s a little

artist wants to do an Arab picture, & has asked me for kit … Do you

think you could provide some from your store?’ – later mentioning in a

letter to Lionel Curtis in 1929 (see below) that the dagger still

remained in the possession of Lady Hilton Young [Scott having married

Edward Hilton Young, later 1st Baron Kennet, in 1922]. No such retrieval was

made, and the dagger and the robes have remained in the possession of

the family since then. (Christie’s).

Lawrence died in a motorcycle accident in 1935 and Lady Kennet died in 1947. This is the only

one of Lawrence’s three Arabian daggers known to remain in private

hands; it’s being sold by the estate of the last Lady Kennet following

her death.

The first silver dagger was given to Lawrence by

Sherif Abdullah, elder brother of Feisal and future ruler of the

Transjordan. Lawrence presented it as a gift to the Howeitat chiefs in

the Wadi Sirhan at the urging of Sherif Nasir - an investment lavishly

rewarded by the support of the Bedouin in the assault on Aqaba,

according to Christie’s.

Lawrence appears with a dagger in many photos, including this one from

the Telegraph article about the auction:

I can't tell which dagger he's wearing. It's not the gold dagger, because the gold dagger is a lot smaller and its front bulges. I think it might be the first silver-gilt dagger, which he gave away in Arabia, as it looks like the

shape’s different from the shape of the dagger in the photo provided by Christie's - the point of the dagger being auctioned curves up all the way to the hilt.

Here's another photo of him in the desert somewhere, taken by B.E.

Leeson in 1917. I can't tell if it's the same dagger here either:

Here's a hand-coloured photo of him from 1917. His dagger is tinted gold, but that doesn't necessarily mean it was gold. It's definitely not the same shape or size as the gold dagger held by All Souls:

His third, smaller gold dagger was sold to his friend Lionel Curtis for £125, and subsequently presented to All Souls’ College, Oxford. Lawrence was a research fellow at the

college from 1919 to 1926. The college still holds a thobe

Lawrence wore, and the canteen set he used during the campaign.

|

| Lawrence's mother gave these robes to All Souls College after his death, in 1938. He adopted Arab dress in 1916 after being requested to when he joined the Arab forces, because he felt he could not gain the trust of the Arabs while dressed as a British officer, and because Arab dress was better suited to the desert. |

|

| Lawrence wore the dagger, discreetly acquired in Mecca in 1917, during

the war; it also appears in the famous Augustus John portrait. He had it

made small because a full-size one would have been too cumbersome. After the war he sold it to pay for repairs to his Dorset

cottage, "Clouds Hill"; in 1938 it was given to All Souls College. Lawrence had purchased the head-dress in Aleppo in

1912 and given it to his mother the following year. He recovered it to

wear during the war because good quality examples were by then hard to

obtain. (source). | | | |

|

| About 1917 Lawrence had a canteen set made in Jidda to his own design. It included the plate, bowl, and spoon which he carried and used throughout the desert campaigns (source). |

|

| A Hittite horse and rider. Lawrence kept the terracotta figure in his room at All Souls

College in Oxford after the war. It dates from the ninth century BC and

comes from the area of his excavations at Carchemish before the war (source). |

I haven’t been able to find a picture of the

sculpture of Lawrence that Christie’s says Kathleen Scott made, or any

other mention of it anywhere, so I’m not sure if it still exists or who might have it. In 1920

Scott did cast a sculpture of T.E. Lawrence’s younger brother A.W.

Lawrence, who was later Cambridge Professor of Classical Archaeology.

It’s a nude statue called "Youth" of a young man with his arms

outstretched, which Kathleen Scott (by then Lady Hilton Young) presented

to the Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge

for the opening of the Institute’s building in 1934.

Lady Hilton Young also presented a number of objects and papers to the

Institute in memory of her first husband and his four companions, who

died on their return journey from the South Pole in 1912. The statue of A.W.

Lawrence

still stands outside the building

(you can see it here. It's a photo of the nude statue from behind). The Latin inscription on its pedestal – LUX PERPETUA LUCEAT EIS – is translated as "let eternal light shine upon them."

oh I love this post.

ReplyDeleteI'd totally wear a keffiyah to the ballet even if I wasn't a Muslim, I've always felt (if I was a dude) Lawrence and I would have got on super well;). Alas, in his time I'd have to have been a Kathleen... :)

It's just such a weird thing to do, especially in post-war London! But I believe you could pull it off :) He must have missed Jordan an awful lot, I don't think he quite knew what to do with himself after the war was over. I can sympathise.

DeleteKathleen Scott seems like a really interesting person, I should do more research on her. There are so many things on my list of stuff to research though, Lord knows if I'll ever get around to it.

Interesting blog, but the jambiya photo at the top of the article does not appear to match that in the Christies catalog, which is gold in color and has a different hilt.

ReplyDelete