In 1763, the VOC (Dutch East India Company) ship Amstelveen was headed from Batavia in the Dutch East Indies (now Jakarta, Indonesia) for Kharj, Iran with a load of mainly sugar and spices when she wrecked off the coast of Oman. From the Cultural Heritage website:

Dr. Klaas Doornbos, a retired professor of education and friend of the Dutchman who discovered Eyks' logbook concerning the Amstelveen in an antique market in Southern France in 1997, has written a book about the wreck of the Amstelveen and the subsequent trek across Oman by the survivors, titled Desert Survival in Oman, 1763: The fate of the Amstelveen and thirty castaways on the South Coast of Arabia. It's set to be published in English and Dutch by Amsterdam University Press in October 2014, but from the news reports it looks like publishing has been scheduled for some years and has not yet happened.

Doornbos explained in The Week in 2012:

According to AUP's website, Eyks' journal is the oldest European account of the coast of Oman and its inhabitants.

The Dutch Embassy to Oman produced a documentary about the trek and the search for the wreck, in coordination with the Ministry of Heritage and Culture.

More from The Week:

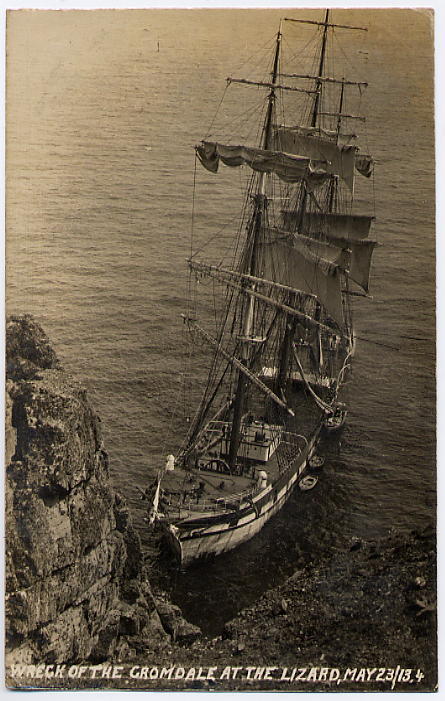

On the 5th of August [the Amstelveen] sailed near Ras Madrakah (Cape Mataraca), on the South East coast of Oman. In the evening, as the darkness was setting in and hampered by the foggy conditions, the ship came too close to the coast and ran aground. Due to the very high and powerful waves crashing on and breaking over the ship, she capsized and broke into pieces and sank. On board were 105 men of which 75 of them drowned. Only 30 crewmen reached the shore alive.

Dr. Klaas Doornbos, a retired professor of education and friend of the Dutchman who discovered Eyks' logbook concerning the Amstelveen in an antique market in Southern France in 1997, has written a book about the wreck of the Amstelveen and the subsequent trek across Oman by the survivors, titled Desert Survival in Oman, 1763: The fate of the Amstelveen and thirty castaways on the South Coast of Arabia. It's set to be published in English and Dutch by Amsterdam University Press in October 2014, but from the news reports it looks like publishing has been scheduled for some years and has not yet happened.

“I am not a professional maritime historian or a cartographer; I am a retired professor. But I was asked to solve the problem of the wreckage. The log that was found was useful, but I couldn’t solve it solely based on that. I used Google Earth and looking at the topography and the map I was able to determine the area where the ship wrecked. We still don’t know the exact location of the wreck because there was no evidence.

The ship was shattered and, I suppose, pillaged later.” Cornelis Eyks was the ship’s third mate and used his talent of writing to keep a detailed log of all the events that transpired from the time the crew set sail from Batavia (Jakarta, Indonesia), headed to Kharg, Iran in 1763.

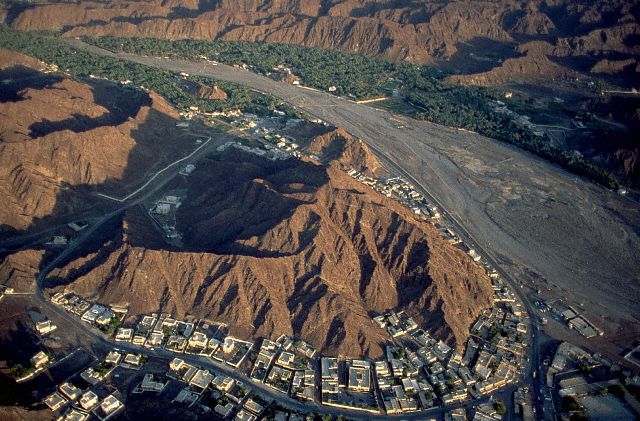

Of the 30 survivors, 22 arrived in Muscat after an arduous trek that took the survivors from Ras al Matrakah, via Duqm, 500km to Ras al Hadd in Sur. After four days of walking, the survivors reached a cape (the cape of Ras al Matrakah), which helped them realise where they were and where they needed to head in order to reach civilisation in Muscat. They reached Muscat 31 days after they shipwrecked, encountering pillaging Bedouins, compassionate nomads, Arabian oryx and giant sand dunes.

According to AUP's website, Eyks' journal is the oldest European account of the coast of Oman and its inhabitants.

The Dutch Embassy to Oman produced a documentary about the trek and the search for the wreck, in coordination with the Ministry of Heritage and Culture.

More from The Week:

I very much hope the book is eventually published, because it is the only source I can find for this story.

The other 30 would make it to a rocky beach in Ras Madrakah south of Duqm and about 20 of those would live through the torturous walk to Sur and Hadd. One of them would faithfully log the story of the survivors of the Amstelveen, a ship whose story ended in Oman and, almost 250 years later, is about to begin once again.

The subject of a new book as well as a whole new chapter in the relationship between the Netherlands and Oman, interest in the Amstelveen was rekindled recently after a chance discovery of a copy of the log kept by the ship’s third mate Cornelis Eyks. Surfacing in an antiquarian bookstore in the south of France, the log came to the notice of Dr Klaas Doornbos who researched it and wrote Shipwreck & Survival in Oman 1763.

A copy of the manuscript is here in Oman in the care of H E Stefan van Wersch, Ambassador of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to Oman but as it has not been published yet, H E van Wersch has promised the author that he will not pass it on, but he was kind enough to narrate excerpts to us.

“The story is like the TV show Extreme Survival, where they drop someone in a remote place and they have to survive with what they can find, only in this case it was a real life or death struggle,” said H E van Wersch. “These men had to walk some 700km to reach a point from which they were taken by sea to Muscat. And this was in August, so you can imagine the heat they had to deal with.

The log describes how at day they would burn in the sun, their feet in terrible shape from walking without proper footwear on hot sand and rock, and at night though drained they could never sleep properly because of the cold. All of this with a terrible shortage of water.”

As not all of them could maintain the same pace, the survivors thinned out into small groups of twos and fours. Some, possibly injured or just unable to go on any further, would drop and have to be left behind never to be seen again. Perhaps due to some misunderstanding in communication, the men came under attack by some of the people they came across in the desert.

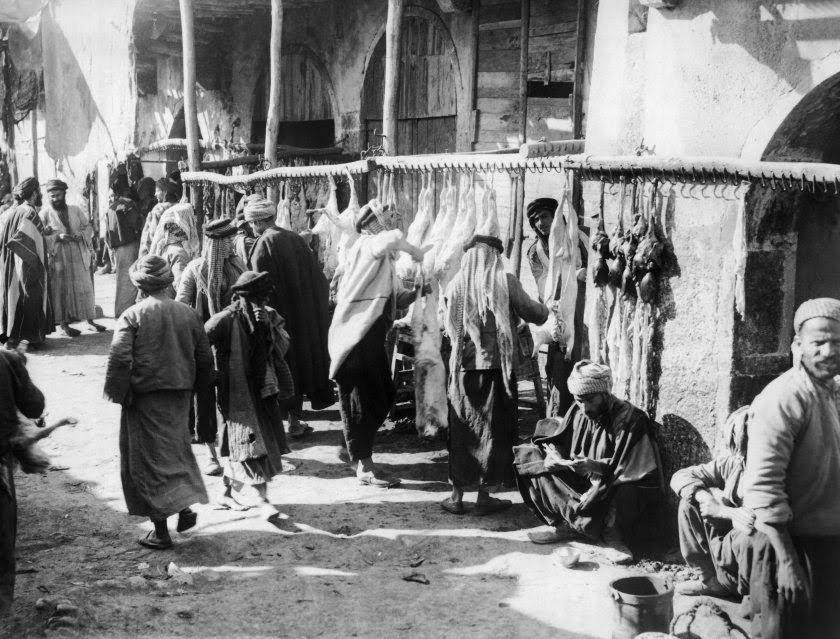

Eyks’ log speaks of being treated with compassion too with some people helping to treat their cracked and burnt lips with some sort of unguent. Some villagers they met also gave them dates and water as well as shelter from the cruel elements to sleep in. “The great thing about the log is what it describes but sadly he leaves so much out. There were many mysteries about the Amstelveen that have not yet been solved,” said H E van Wersch.

One mystery is why it ran aground in the first place. The captain was experienced and would have known these waters. Another enigma is the man whom Eyks met in Muscat who spoke fluent Dutch - he would surely have asked how the man had learnt Dutch but has not recorded that. Some of the anomalies caused the whole wreck story to be treated with suspicion by the Dutch East India Company who suggested that the crew might have fabricated the story and sold off the cargo.

Not sympathetic to the harshness endured by the men, the company sent Eyks to Kharg where he was questioned and from there back to Batavia for another round of interrogation before finally buying his story and paying him his back salary but only up till the day the ship was wrecked. As to the treasure the Amstelveen was carrying? A load of mainly sugar and spices, so there is not much in those rough waters to go diving for - other items such as the cannons, which commanded a good value in those days, would almost certainly have been salvaged shortly after the wreck by whoever learnt about it.

.jpg)